Being everyone’s friend and nobody’s enemy. (Re)Discovering Oman’s go-between role

Keeping in mind the intertwining of domestic and international dynamics, Oman’s interest in not getting entangled in regional struggles is deemed functional in countering possible destabilizing spillover effects across the country. The recent high-level official visit to the Omani capital by the Iranian president, Ebrahim Raisi, well exemplifies the Sultanate’s high priority in maintaining cordial relations with Tehran.

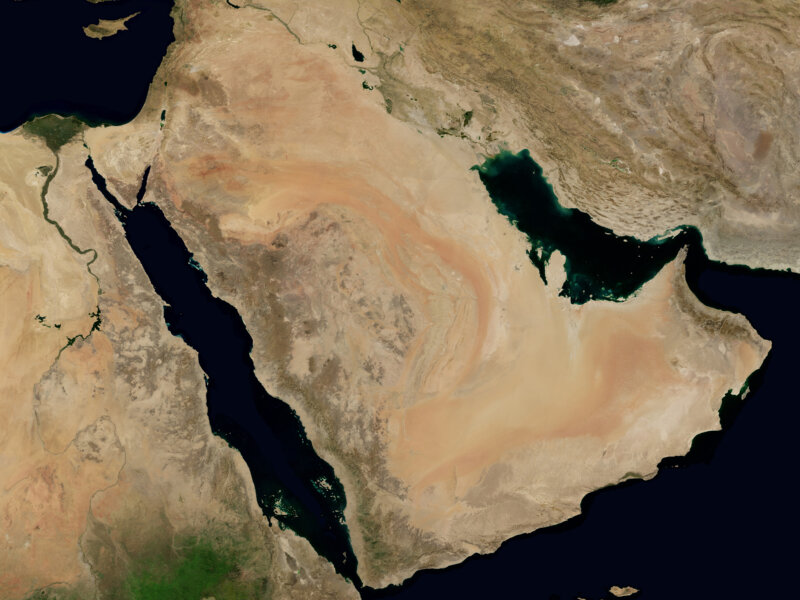

At the crossroads between the Strait of Hormuz, the Arabic Sea, and the Indian Ocean, the Sultanate of Oman has the potential to become a new geographical space where Sino-American interests could collide. Amid Washington’s concerns in seeing Oman rising to logistical support for the Maritime Silk Road Initiative, the Chinese Defense Minister’s recent visit to Muscat to discuss with Oman’s Deputy Defense Minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs the bolstering of bilateral ties between the two countries has put even more in the spotlight how Beijing is looking at Muscat to increase its influence in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

As an easy entree to both Indian and Eastern African markets, Omani ports are at the core of foreign geostrategic and geoeconomics stakes. It is not by chance that in March 2019, Washington signed the Strategic Framework Agreement with Muscat, aimed at governing the U.S. access to facilities and ports in Salalah and Duqm. China’s investment in the Duqm Special Economic Zone – a mega-development project as part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative – is another striking example of the strategic growth of Oman’s coastline in the geopolitics of global powers.

From Oman’s side, the country’s interest in enhancing the partnership with China also in non-oil sectors (renewable energies, digital economy, and maritime infrastructures among others) without turning its back on the traditional Western allies, namely the US (and the UK), has to be framed within Oman’s “Vision 2040”. Launched by the new Sultane Haitham bin Tariq Al Sa’id in 2021, this blueprint for the country’s economic and social development has been welcomed as the gateway to keeping pace with domestic, regional, and global dynamics, and pushing Oman toward greater integration in the global market.

In this regard, Haitham bin Tariq Al Sa’id has embraced Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id’s legacy, embedding his political and socio-economic vision. The “father” of the Omani’s Nahda (“renaissance” in Arabic) focused its mandate on transforming Oman from a pre-modern state to a prosperous and developed country, with an emphasis on economic diversification and more investments in the private sector. Oman is still heavily reliant on oil and gas exports, which accounted for roughly 63% of the country’s income in 2021. Against a global backdrop featured by the Covid-19 pandemic and the volatility of the crude oil market, Muscat needs to invest in the non-oil sector to address its socio-economic hardship.

It is noteworthy that the broadening of economic and diplomatic relations also serves Oman’s security needs. Indeed, Muscat’s independent and balanced foreign policy – summed up in one sentence: “being everyone’s friend and nobody’s enemy” – seems to stem from the assumption that security and territorial integrity cannot be split up from the external environment the country is embedded in. Therefore, a less turbulent regional setting is perceived by political elites as functional for achieving domestic stability and bolstering Muscat’s economic performance.

Therefore, against the backdrop of a highly unstable regional landscape characterized by internationalized conflicts (e.g., Syria, Libya, and Yemen) and rivalries not yet appeased (the geopolitical struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran), it is not by chance that Muscat is keen to become an important player and rise to the role of regional facilitator and mediator. Its official adherence to the Ibadi branch of Islam could also be a key feature of the Sultanate’s geopolitical profile as a credible peace broker. In this regard, Oman’s allegedly current behind-the-scenes work in Vienna’s negotiations for the revival of the JCPOA, in the Yemen dossier, and in the ongoing Saudi-Iran talks are three striking examples of its go-between role in the Gulf region.

In the case of Yemen, since the beginning of the civil war in 2015, by taking advantage of friendly relations with both Ansar Allah (aka Houthis) and the major regional actors engaged in the conflict, Oman hosted several times formal and informal talks between the internationally-recognized Yemeni government led by the former President ʿAbd Rabbih Manṣūr Hādī; the Houthis; the Southern Transitional Council; the Saudis, and its allies. The recent release of the 14 detainees held by Ansar Allah, as well as that of the Emirati-flagged ship Rwabee, has provided further evidence of current Oman’s mediation efforts in the Yemen war.

From Oman’s perspective, threat perception in the Gulf will never be reduced until constructive dialogue among the key regional players will not kick off. In this regard, the revival of the JCPOA is deemed to be a crucial transitional step toward regional détente. Already in 2012, Muscat was functional in paving the way toward the Vienna talks and the adoption of the 2015 agreement. Now that nuclear talks are entering their final stage, the meeting between Oman and Iran foreign ministers in Tehran on 23 Feb. 2022, has raised speculation on Muscat’s yet another engagement as a facilitator between Iran and the US.

Thus, at the forefront of promoting reconciliation and comprehensive understanding among the two banks of the Gulf, Oman was also very important, along with Iraqi Prime Minister Al-Kadhimi, in the resumption and the setting up of the fifth round of direct talks between Tehran and Riyadh in Baghdad. Indeed, the country had hosted preliminary technical meetings between high-level officials of both parties, and it is expected that it will continue to be central in the ongoing Saudi-Iran détente. As previously mentioned, strategic considerations in terms of safeguarding Oman’s internal stability should be counted to explain Muscat’s diplomatic engagement.

Houthis’ attacks against civilian infrastructures in Abu Dhabi have clearly illustrated that conflicts do not know territorial boundaries. Therefore, keeping in mind the intertwining of domestic and international dynamics, Oman’s interest in not getting entangled in regional struggles is deemed functional in countering possible destabilizing spillover effects across the country. A similar argument could be applied to explain the Sultanate’s high priority in maintaining cordial relations with Tehran. Indeed, the two countries manage the sealines for international trade across the Strait of Hormuz, a strategic chokepoint through which roughly a third of global seaborne oil trade flows.