Med-Or Monthly Africa Report October 2025

Online the first edition of the monthly report on Africa.

Editor’s Note

This first edition of Med-Or Monthly Africa Report opens with a reflection on the shifting foundations of the continent’s economic and strategic landscape. From the mounting pressure of debt and fiscal stress to new frameworks for mineral governance and infrastructure, Africa is asserting a more central role in shaping global trends.

Across the continent, there is the need for not only relief but reform - approaches that combine financial responsibility with sovereignty, resource control and regional cooperation. Ethiopia’s completion of the GERD, the revival of the Tanzania–Zambia Railway, and the Democratic Republic of Congo’s new cobalt regime each reflect this wider rebalancing of power.

For Italy and Europe, these developments underline both a responsibility and an opportunity: to engage with Africa as a partner in shared growth, stability and innovation. As Med-Or continues to explore these connections, the Med-Or Monthly Africa Report will aim to provide insight into the ideas and dynamics that are shaping the continent’s future.

A special mention to Giuseppe Mistretta, former Italian Africa Director at the Italian Foreign Ministry, whom we are honoured to have taken the lead in initiating and coordinating this exercise, and Vera Songwe, a leading African economist, for her contribution to this monthly report.

Umberto Tavolato

Director for Special Projects

Med-Or Italian Foundation

The African Debt Issue and Proposals to Alleviate it

Giuseppe Mistretta

Africa’s debt remains a central challenge. It shapes the continent’s development prospects and affects the stability of global financial markets.

According to the World Bank, IMF, UNCTAD and AfDB, Africa’s total debt reached about USD 1.16 trillion in 2024, equal to roughly 75 per cent of its GDP. At the current rate, it could climb to USD 1.3 trillion by 2028.

Higher global interest rates between 2021 and 2023, following the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, have worsened the burden. African countries now spend around USD 75 billion each year on interest payments alone. That is almost 15 per cent of their budgets - more than most spend on health or education.

Zambia, Ethiopia and Ghana have already defaulted. Others, including Kenya, Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa, face serious fiscal stress. Yet most continue to repay their debts to avoid downgrades and maintain access to international credit, even at the expense of investment and growth.

Some states are again turning to the bond markets, hoping to benefit from slightly lower rates and rising commodity prices. Angola has done so, and others, such as Nigeria, South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo, may follow. But much of this new borrowing will be used to service existing debt, not to fund development.

Among the most ambitious ideas to address the crisis is the Jubilee Commission, launched by Pope Francis for the 2025 Jubilee Year. Led by economists such as Joseph Stiglitz, Vera Songwe, Jeffrey Sachs and Martin Guzmán, it proposes a new framework for shared responsibility between debtor and creditor nations.

Key recommendations include:

- Joint accountability between lenders and borrowers, recognising debt as a global issue.

- An impartial mechanism for managing sovereign insolvency, similar to national bankruptcy courts.

- Public multilateral rating agencies to reduce dependence on private Western firms.

- A clearer distinction between productive and non-productive debt, prioritising loans that drive growth.

- Support for temporarily illiquid states with sound long-term prospects.

- Regular suspension mechanisms for debt servicing, like the G20’s 2020 DSSI initiative.

- More frequent IMF Special Drawing Rights allocations to boost liquidity.

These proposals demand stronger multilateral cooperation and fairer global rules. Without such reform, the system will remain shaped by unilateral interests and the power of the few.

Managing Low-Income Country Debt under Global Fiscal Stress

Vera Songwe

The persistence of debt distress across low- and lower-middle-income countries, despite decades of relief efforts, should concern everyone. It suggests either the problem is deeply entrenched, or that the remedies have failed. There is also a third factor rarely discussed: the caregivers themselves are now unwell.

As the World Bank and IMF meetings close in Washington DC, there is broad consensus that the crisis must be tackled collectively. Reports such as the Jubilee Commission, the UN Secretary-General’s Seville FFD report, and Healthy Debt for a Healthy Planet outline what should be done. The challenge is not ideas but implementation - and the worsening conditions countries now face.

Finance ministers from developing countries this week called for action on five fronts:

1. Integrate climate and nature into fiscal policy. Reform IMF and World Bank debt frameworks to create fiscal space for climate resilience spending.

2. Ease debt pressures by reducing the cost of capital and expanding access to concessional finance for refinancing and servicing debt.

3. Link debt and climate action. Scale up tools like contingency clauses and debt-for-nature or debt-for-climate swaps, allowing countries to redirect repayments toward sustainability in exchange for longer maturities and lower costs.

4. Mobilise private capital through guarantees and blended finance. Development banks such as CDP can help lower risk and attract investors, but this requires additional resources.

5. Build capacity for sustainable debt management. Establish a “one-stop shop” for advice and training, drawing on both South–South learning and lessons from advanced economies like Italy and Spain that have successfully exited debt crises.

Tese steps are straightforward in principle, but difficult in practice. Advanced economies remain divided over how much to spend on resilience, even as extreme climate events multiply. The earthquakes and floods in the Philippines and the record heat in southern Europe are reminders that ignoring these costs is like balancing a household budget while pretending electricity is free.

High and rising public debt in the G7 leaves little fiscal room to support others. In countries such as the United States, Japan, France, Italy and the United Kingdom, interest payments now absorb 3 to 4 per cent of GDP - exceeding aid budgets. Japan alone will pay over USD 400 billion in interest this year, more than ten times its development aid. China, once a key source of investment for the Global South, is also slowing due to internal economic strains and trade tensions with the US.

These trends create a “triple bind” for developing economies. Investors can earn good returns in safer markets, G7 governments have no fiscal space to transfer resources, and rising global rates make existing debt even harder to service. Many low- and middle-income countries borrowed when capital was cheap; now they must repay at far higher costs.

Discussions in Washington focused on rebalancing the global economy. The G7 and China were urged to restore fiscal discipline, revive domestic demand, and spur innovation to reignite growth and lower the cost of capital. Without that macroeconomic correction, progress on debt relief will stall.

Developing countries, meanwhile, must strengthen domestic resource mobilisation, attract private investment, and support new allocations of IMF Special Drawing Rights. Combined with genuine collective effort, these steps could finally begin to ease what has become a stubborn and recurring refrain: the debt distress of the world’s poorest nations.

The Horn of Africa after the Inauguration of the GERD Dam

Adi Guyo

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), inaugurated on 9 September, stands as Africa’s largest hydroelectric project and a landmark achievement for Ethiopia. A feat of engineering and a symbol of ambition, it embodies Ethiopia’s determination to secure energy independence and regional influence, with far-reaching geopolitical consequences.

More than an infrastructure project, the GERD is a declaration of sovereignty and self-reliance. Over 90 per cent of its financing came from domestic sources through bonds, salary contributions and lotteries, with limited foreign input, chiefly from China. This has fostered a strong sense of national pride and unity in a country still grappling with ethnic divisions and political instability.

Economically, the dam could transform Ethiopia and its neighbours by narrowing the energy gap, driving industrial growth and deepening regional integration through power exports. These gains, however, depend on expanding electricity transmission networks within Ethiopia and across borders to ensure the benefits are widely felt.

The GERD’s completion without a binding regional agreement has redrawn the geopolitics of the Nile Basin. Egypt continues to rely on the 1929 and 1959 treaties, which excluded Ethiopia and granted Cairo veto power over upstream projects, a position Addis Ababa rejects. The 2015 Declaration of Principles encouraged cooperation but lacked legal force, and subsequent talks broke down over drought management. In 2024, upper riparian states ratified the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework, but Egypt and Sudan refused to join. With the GERD now fully operational, Ethiopia enters future negotiations from a position of strength.

Climate change complicates the picture. The Blue Nile, which originates in Ethiopia, is crucial to the river’s flow, but rainfall has become increasingly unpredictable. The GERD can mitigate floods yet may also restrict downstream water during droughts. Without transparent coordination, future releases could heighten tensions, as seen in Sudan’s October flood following heavy rains in the dam basin. Ethiopia’s growing energy needs and Egypt’s dependence on the Nile make the situation delicate. Although the United States has pledged renewed mediation, earlier efforts achieved little.

The dam’s success has also emboldened Ethiopia’s foreign policy, especially its ambition for direct access to the Red Sea. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has explored three possible routes: through Eritrea’s Port of Assab, via agreements with Somaliland, or through a commercial corridor to Somalia. Each carries risk. Talks with Eritrea have rekindled old rivalries, and Egypt appears poised to align with Asmara if tensions rise. Renewed conflict would have catastrophic consequences. Engagement with Somaliland has slowed following mediation by Türkiye and the 2024 Ankara Agreement, while security challenges have hindered progress with Somalia.

Domestic politics remain a key variable. Frictions surrounding the implementation of the 2022 Pretoria Memorandum, which ended the Tigray war but left lingering mistrust between Addis Ababa and Asmara, continue to shape Ethiopia’s internal stability. Whether the GERD becomes a catalyst for national cohesion or a source of new divisions will depend on how these dynamics evolve.

Amid shifting alliances, external powers such as the Gulf States, Turkey, Russia, China and Iran, are pursuing their own interests. For Africa and Europe, the priority should be preventing the use of force and upholding international law and the principles of the UN and AU charters. The GERD could yet become a platform for cooperation and shared growth, but only if regional actors choose dialogue over confrontation.

Tanzania-Zambia Railway, Lobito Corridor and Zambia

Corrado Čok

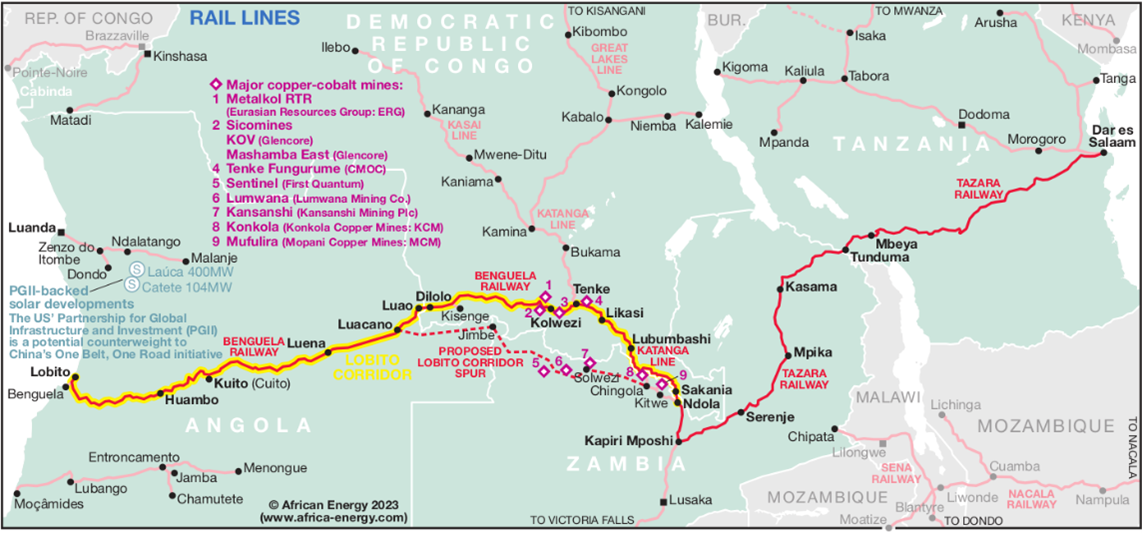

On 29 September, a major Chinese infrastructure developer signed a USD 1.4 billion deal with the governments of Tanzania and Zambia to revitalise the railway linking the two countries. After years of neglect that reduced transport volumes, the project is expected to quadruple traffic within two years.

Built in the 1970s, the Tanzania–Zambia Railway (TAZARA) is a historic symbol of Africa–China relations. It was Beijing’s largest overseas infrastructure project at the time and remains highly symbolic today. Under the new agreement, the state-owned China Civil Engineering Construction Company (CCECC) will modernise the 1,860-kilometre line for USD 1 billion and operate freight services with new trains worth USD 400 million. The deal grants CCECC full operational control under a 30-year concession. At the same time, China Harbour Engineering Company has upgraded the port of Dar es Salaam with a new terminal and expanded facilities.

Stretching from Zambia’s copper-rich heartland to the Indian Ocean, TAZARA is vital for transporting copper and cobalt to global markets, especially China. These minerals are essential for electric vehicles, renewable energy, aerospace and defence. China dominates the global value chains for both - over 40 per cent of copper processing and nearly 80 per cent of cobalt refining.

The relaunch of TAZARA will support new mineral ambitions in Southern Africa to increase production and trade in the sector. Logistics in the region remain the major challenges with limited roads, that creates congestion and high transport costs. As mining investments expand, exports are rising, intensifying these bottlenecks. Chinese mining companies, which have invested about USD 3.5 billion in Zambia, pledged a further USD 5 billion last year to boost copper and cobalt production by 2031. With the Democratic Republic of Congo now restricting cobalt exports through new quotas, Zambia’s role in China’s supply chain has become even more critical.

Other powers are also competing to build new corridors across the region. Japan and the African Development Bank have pledged USD 7 billion to develop the Nacala Corridor from Zambia to Mozambique, while the United States and the European Union are backing the Lobito Corridor, linking Zambia and the DRC to Angola. While TAZARA will link Zambia to the Atlantic Ocean, Lobito is intended to anchor Zambia’s mineral investments, including from the US, to the Atlantic Ocean.

Zambian President Hichilema has launched political and regulatory reforms aimed at transforming the mining sector from a traditional extraction-based model into one focused on adding value to resources through processing activities, the development of industrial plans, inclusive growth, and strategic partnerships designed to diversify the economy and attract new investors. These policies have already led to more than $6.5 billion in new investments in the sector, including significant contributions from several Western and Gulf countries.

Shifting Advantages under Congo’s New Cobalt Regime

Luciano Pollichieni

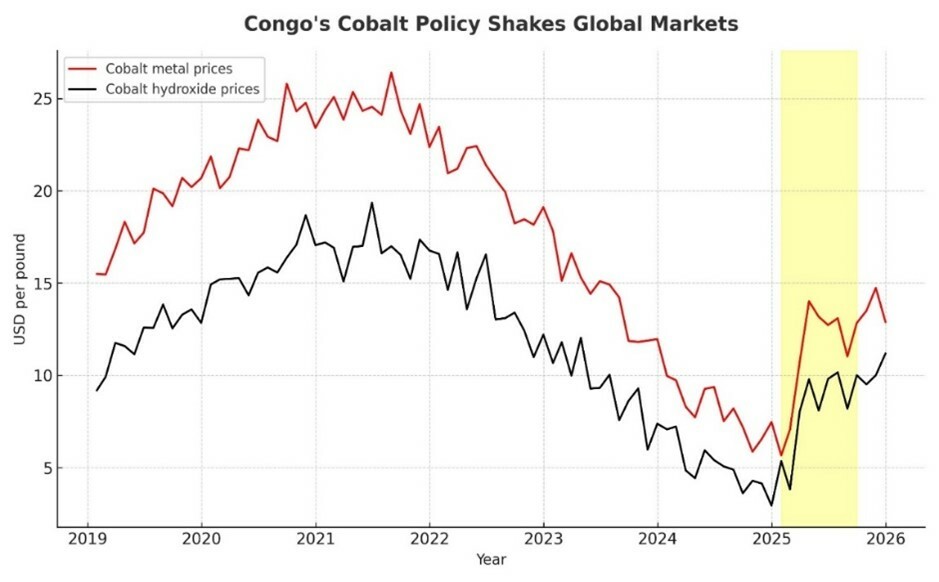

In just seven months, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) reshaped a critical global market. Between February and September, Kinshasa’s temporary export ban on cobalt – the metal at the heart of electric vehicles, batteries and digital devices – sent prices up by an estimated 50 to 70 per cent. The ban has now been lifted and replaced with a quota system that formalises state control over one of the country’s most strategic resources.

The new regime caps cobalt exports at 18,000 tons for 2025, rising to 96,600 tons in 2026 and 2027, and creates a 9,600-ton strategic reserve managed by the newly formed ARECOMS. After military setbacks in North and South Kivu, where M23 still holds key mining routes, President Félix Tshisekedi is using cobalt policy as an instrument of sovereignty – reinforcing authority at home and bargaining power abroad.

Through ARECOMS, the government can now allocate export rights and the strategic reserve according to national priorities, potentially directing supply toward local producers and industrial projects. If implemented with credible oversight, the framework could formalise parts of the informal trade, drawing artisanal and rebel-linked operators into regulated channels and turning economic inclusion into a tool for stability. Producers in Zambia, Zimbabwe and Tanzania are watching closely and may consider similar systems, reshaping price dynamics and strengthening Africa’s collective leverage.

The policy also opens the door to new players. By capping volumes long dominated by Chinese companies, Kinshasa has lowered barriers for American firms. The move aligns with President Tshisekedi’s gradual pivot toward Washington, seen as both political insurance at home and strategic reassurance abroad. Yet the United States remains cautious. While the conditions favour deeper engagement, the Trump administration has not clarified its financial commitments to the Lobito Corridor or wider DRC projects. Without clear funding, the US risks setting the agenda without following through.

At home, the quota system strengthens Tshisekedi’s political control. ARECOMS now acts as regulator and gatekeeper, deciding who benefits from export rights and access to the strategic reserve. This makes cobalt governance both an economic and political tool. It also gives Kinshasa a lever to stabilise prices or trade access for infrastructure, investment or security cooperation. The question is whether this power will be used to consolidate patronage networks or to build a transparent, rules-based system.

For China, the new regime marks a clear setback. Its operators once dominated Congolese cobalt flows, absorbing roughly 120,000 tons per year. The export caps disrupt that dominance and strain feedstock for China’s refining industry. Beijing will likely seek exemptions through diplomacy while accelerating its shift downstream into refining and battery manufacturing, where efficiency and scale still give it an edge. In parallel, China continues to invest in regional infrastructure, such as the revitalised TAZARA railway, maintaining strategic depth even as its upstream control weakens.

For Tshisekedi, the quota policy serves both economic and diplomatic ends. It allows him to renegotiate relations with Beijing on more equal terms, including the long-contested 2008 “infrastructure-for-minerals” deal. The winners will be those able to turn opportunity into institutions – combining speed, credibility and strategic foresight.

For Europe, the change is a test of ambition. With China’s exports constrained, there is space for a more balanced engagement. European investors can partner with Congolese firms in processing, logistics and value-added industries. Success will depend on rapid action and regulatory clarity. Italy, through its €250 million investment in the Lobito Corridor via the Africa Finance Corporation, is one of the few countries already moving from declarations to delivery. The DRC’s new cobalt framework could become a cornerstone of a European-led network of responsible critical-mineral supply chains. If pursued with coherence and urgency, it offers Europe a rare chance to shift from dependency to partnership – and to help shape a fairer, more stable global cobalt economy.

Authors

Giuseppe Mistretta

Former Director for Sub-Saharan Africa at the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, and ex Ambassador to Angola and Ethiopia

Vera Songwe

Economist, Chair and Founder of the Liquidity and Sustainable Facility (LSF), and Non-Resident Senior Fellow at Brookings

Luciano Pollichieni

Senior Analyst, Med-Or Italian Foundation

Corrado Čok

Expert on the Horn of Africa, Med-Or Italian Foundation

Adi Guyo

Junior Analyst, Med-Or Italian Foundation

Dan Morland

Senior Media & Communications Consultant, Med-Or Italian Foundation

Asja Amail

Officer for International Relations and Special Projects, Med-Or Italian Foundation

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE PDF